General Academic Assembly 2019

What “The University the World Needs” Needs from Us

By Peter StoicheffI begin by acknowledging that we are on Treaty Six territory and the traditional homeland of the Metis. We pay our respects to the First Nations and Metis ancestors of this place and reaffirm our relationship with one another.

In previous GAA remarks I’ve spoken about the need for universities like ours to push a change agenda. Our new University Plan now confirms that position, and I thank all of you for contributing to make it unique, creative, future-oriented and outward-looking. I thank all the colleges, schools and units for their Plans, which align so creatively with the University’s; they’re bold and visionary, as befits the ambitions of this great university.

In the process of creating these Plans, we have focused our energies and resources, and implicitly rejected being everything to everyone. We have identified our strengths and our commitments for the next six years so that we can move the needle on them in the interests of having the greatest impact beyond ourselves we can have – a sort of USask version of “Tidying Up With Marie Kondo.” And as with her “Life-Changing Magic”, so too with ours, we need to embrace and pursue change.

What kind of change are we talking about?

Universities have existed in the western world for almost 1,000 years. In some basic ways they haven’t changed much over that time. Today’s convocation ceremonies with their academic gowns and pomp mimic the ecclesiastical and judicial spirit of the medieval university. Today’s lecture halls with one sage on the stage do the same. Of all the institutions we have in the western world and have had for centuries – clergy, nobility, commoners (the original three estates), the press (the fourth estate), medicine, the judiciary, business and education – universities have remained relatively unchanged by the disruptions that have swept through the others. Journalism, for instance, has been transformed by social media, by technological advances in transmitting information, and by skepticism of journalistic authority. Closures of newspapers have been rampant and will continue; many media outlets are shadows of their former selves. Facebook is the world’s largest media empire yet it creates none of its own content. Universities, however, have been relatively immune to all this.

Whether or not the University of Saskatchewan meets this challenge will affect the quality of our programming, our levels of public support, our student enrolments, our relevance to Indigenous communities, our funding both private and public, our research productivity, the level of innovation in Canada, and ultimately – in a post-truth world – our contribution to the moral fabric of the country and the globe.

There’s no doubt universities already serve important purposes in Canada. At first glance, it might seem that, because they do, not much change is needed. There are 1.7M students at Canada’s 96 universities. 1.6M new jobs were created between 2008-2017 for university graduates -- three times those created for graduates of all other types of postsecondary education combined. Canadian universities are a $35B enterprise in direct expenditures. Of this total, the members of the U15 (like us) have the bulk of the impact because of the research they do – typically at least twice the economic impact of non-U15 universities.

The research conducted in many parts of the university this past year contributes to this. This past year’s examples include the fact we’ve opened a one-of-a-kind-in-the-world Livestock and Forage Centre of Excellence -- a research facility focused on improving the efficiency and profitability of beef production in Saskatchewan and beyond. It harnesses the expertise and interdisciplinary connections of partners and key stakeholders in industry and research. Our Sylvia Fedoruk Canadian Centre for Nuclear Innovation received federal funding to renovate its innovation wing to conduct leading edge imaging research that will improve detection of cancers and other diseases. Our VIDO-InterVac received major federal funding to begin manufacturing vaccines, not just inventing them. We’ve built the Collaborative Science Research Building with a $30M federal Strategic Innovation Grant; it will bring together researchers from many disciplines to help solve complex challenges.

We were successful last year in the federal government’s Canada 150 Research Chair program – one of approximately two dozen universities to be successful – designed to attract research talent from outside Canada and to take advantage of Canada’s attractiveness for scholars in the midst of global uncertainty like Brexit and U.S. politics. Dr. Jay Famiglietti left the NASA Jet Propulsion Labs to come to our Global Institute for Water Security as a Canada 150 Research Chair. This past year four of our faculty were inducted into the Royal Society, and one into the College of New Scholars – the highest number in one year we’ve ever seen. We received four Vanier scholars at the graduate level – three of them Indigenous – again the highest number we’ve ever seen. Dr. Carrie Bourrassa and the CIHR Indigenous Peoples Health Institute relocated here from Ontario; Dr. Alexandra King joined us as the Cameco Chair in Indigenous Health the previous year after a search lasting over a decade. Eleven of the twelve Saskatchewan Health Research Fund major achievement awards went to USask researchers. It is not surprising that our TriCouncil success rates are up, that our national CIHR success rate and submission numbers were at historic highs, and that Research Infosource, ranking Canada’s Top 50 research universities, raised us from 13th out of 50 last year to 11th this year. One of our faculty members, Dr. Regan Mandryk in Arts & Science’s Computer Science department received NSERC’s prestigious EWR Steacie Memorial Fellowship – one of only six faculty in Canada to do so – which celebrates the achievements of young scientists. Stay tuned for more announcements regarding this kind of success here shortly.

With all this research and applied science activity we attract thousands of researchers, students, postdocs and faculty from around the world to work and study here – so many, in fact, that we needed to build a hotel to ensure they could find accommodation – so we did, and opened it this past year.

In these respects and more, we are already fulfilling our UPlan commitment to “unleash discovery” and “confront humanity’s greatest challenges and opportunities.”

In addition to this, ninety-six percent of our graduates get jobs upon graduation, thereby contributing to the economy; and when you consider that our enrolment numbers, flatlining a few years ago, have now increased by between 1% and 3% annually in recent years, that contribution will become ever more significant. This year, our student numbers are up by as much as 3%; we’re at over 25,000 students this year and well on our way to our goal of 28,000 by 2025. Indigenous student graduation numbers and enrolments are higher than ever before.

Our new campus to be opened in Prince Albert in 2020 will support the local economy there. It’s an example of us continuing to think big in the face of economic challenges this past year, and I thank all of you for doing that. The Prince Albert building will attract many students from the area and north who might otherwise not have access to our Saskatoon campus, and likely the majority of those students will be Indigenous.

So what’s to change?

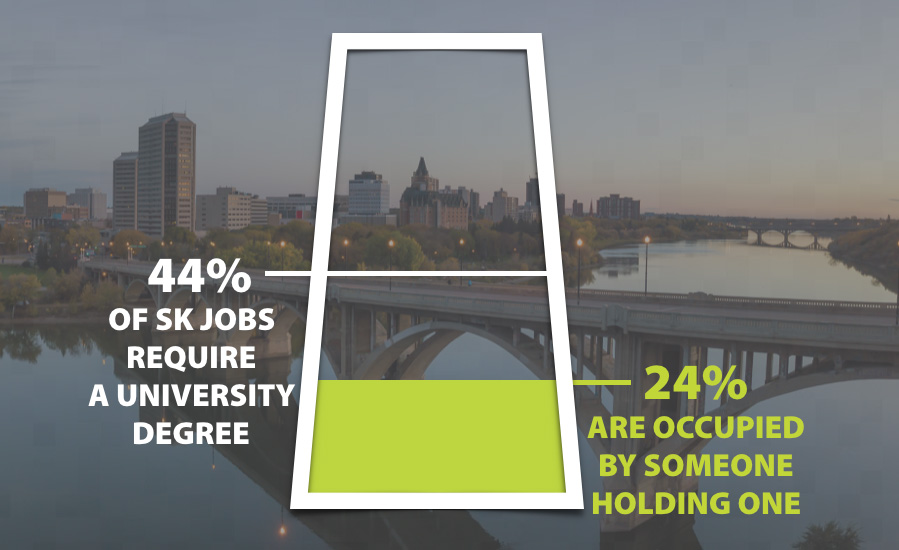

There is a constant need for even more of our graduates in this province. Forty-four percent of SK jobs require a university degree, yet only 24% are occupied by someone holding one. This means we must understand and respond better than we currently do to the province’s employment needs. This is a challenge for all universities in Canada. Although universities do not exist primarily to satisfy the specific requirements of the labour market, they do need to understand that occupations, professions and career patterns are changing at a rate we’ve never seen before. Merely keeping pace instead of falling behind means change for us; leading in this regard means substantially altering our modes of and attitudes towards external engagement.

On the flip side, many new jobs are being created by the advanced technologies that are causing that to happen; and those advanced technologies are products of university research or university training. And new jobs are opening up that five to ten years ago no one would have predicted would even exist. This means that people in careers will need to change what they do and what they know. Here, too, universities like ours can help, by building a culture of lifelong learning, upskilling, and skills fitness.

Change involves being responsive to employment needs, to disruptive technologies and their effects on the workforce and to upskilling the continual supply of people whose automated jobs have made them redundant.

Universities in Canada must respond by becoming more permeable – accessible by employers who can help identify the future of job creation so that universities can better align programming to new employment needs. Sixty-five per cent of students at Canadian universities are involved in work-integrated learning programs; closer to 50% of our students are. The federal government believes we should be striving for 100%, and business agrees. Here as well, our UPlan positions us for change; one of our guideposts is to ensure “new and enhanced applied learning experiences for students”. Last month’s federal budget responded to this by creating 84,000 new student work placements by 2023 through an almost $800M investment. We must take advantage of this.

We should also be striving to increase the number of our students who study abroad. Students need to study internationally, to become globally engaged citizens fluent with other cultures and ways of being. Yet only 3% of Canadian university students in any given year travel abroad to further their studies, and USask students are no different. By comparison, most countries in the developed world see many more of their university students take advantage of study abroad opportunities. Federal budget 2019 pledges $148 million over five years toward a new International Education Strategy, which includes an outbound student mobility pilot program providing international work and study opportunities. The funds would also go toward promoting the merits of Canada as a destination of choice for international students. Our International Blueprint has the goal of increasing outbound student mobility by 35%, bringing our total percentage of students studying abroad closer to 5%, a realistic and important aspiration we need to make good on.

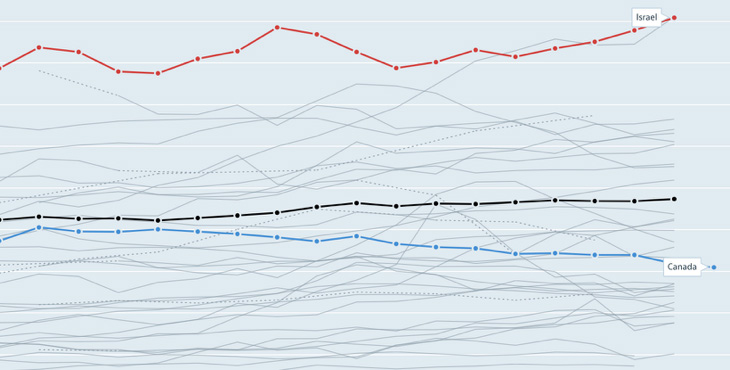

Being more permeable also means connecting organizations and companies with our research capacities. Our UPlan requires us to pursue “growth in commercial outcomes”. Currently, universities are complex beasts to most outside of them. If a company has a research need, it is not easy for it to know how to find what it needs at a university. The universities and business sectors in many countries do this better than Canada does. Israel is an example of one whose university and business sectors are well connected; Canada has a lot to learn from it and others about how to increase research productivity and innovation. The opportunities for this exist in our own backyard. Our Strategic Research Plan (“Discovery the World Needs”) seeks increased engagement with startups and businesses in the adjacent Innovation Place research park by faculty, research fellows and students. The potential of such an innovation corridor here is tremendous, and I say this partly because last year our Innovation Enterprise unit worked with more ideas, people and market research projects than ever before.

Canada is in the bottom third of the thirty-six OECD countries for R&D spending as a percentage of GDP; we’re behind countries such as Slovenia and the Czech Republic.

We are only slightly ahead of Estonia, Italy and Portugal. Our innovation ranking is about the same, and has been dropping. Israel, far ahead of us, is at the top. It has no natural resources, and is situated on a desert with no fresh water. Instead, as the father of Israeli startups said to me when I visited Israel last year, their natural resources are between their ears. Nevertheless, it leads the world in innovation, start-ups, and R&D investment. Israel has the highest number of startups per capita of any country in the world, earning it the title of “startup nation”. It is not risk-adverse; it educates its university students to learn from failures instead of succumbing to them; it connects university research with the country’s many needs and challenges. Canada, rich in natural resources, relatively secure militarily, risk-adverse, and conservative by nature, does not experience the imperative of innovation, and it shows.

Universities such as ours have a major role to play in turning this around. Canada does not have an ecosystem of industry labs the way the US does – research universities supply this strength in Canada. If there are going to be disruptive research breakthroughs here, they’re going to be driven by universities like ours. The challenge is to connect up universities and industry, business, not-for-profits, communities and all other sectors whose futures depend on the knowledge economy. Here, too, our UPlan is predictive: it commits us to be “viewed as an accessible, go-to resource by partners and stakeholders in Saskatchewan and beyond”.

An example of how we are doing this involves our Global Water Futures research program, funded by the federal Canada First Research Excellence Fund. It involves us with 335 partners including fiteen other universities and $292M in funding; 162 faculty investigators and almost 500 researchers have been hired as a result; and is has generated six new Indigenous community water projects, each co-led by an Indigenous community.

Other examples from this past year of disruptive research serving community needs includes a new flagship SSHRC program to re-imagine Energy Security involving an international and multisectoral partnership with northern and Indigenous communities from the Circumpolar North. We have a new flagship program in the Cannabis Research Initiative of Saskatchewan, a unique interdisciplinary exploration of potential new strains of cannabis for medical use. And we are investigating in emerging areas such as revitalizing agriculture on Indigenous lands and ensuring safe water supplies and sustainable communities.

An example of Canada taking things in this direction is the federal Superclusters program, which identified five areas in which the country had particular expertise and capacity for global impact: Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, Advanced Manufacturing, Ocean Sciences and, here, Protein Industries. The world will need to increase its food supply transformatively if it is to satisfy its growing future population. All the world’s protein needs cannot be met in the form of meat, leaving plant protein as a major contributor. But plant protein production needs to be far more efficient, and effective in globally varied environmental conditions, if it is to be the game-changer it needs to be. The Protein Industries Canada supercluster, based in Saskatchewan, is Canada’s response to this challenge. It is led by industry and supported in its research by the UofS, its most significant research partner. Our Global Institute for Food Security is our flagship research centre in this area. Researchers in it and the College of Agriculture and Bioresources were key members of an international consortium that has successfully mapped the wheat genome this past year – an example of disruptive research that only great universities can provide.

And the connectivity I’m speaking about isn’t just with those sectors; we need to respond, at the faculty level, to the current significant issues of the day. Our UPlan directs us to do just that, by acquiring “Heightened public and private-sector recognition of the impact of our work in the region, the province, the nation, and the world”. We’re often seen to be engaging with current issues that universities can play a role in helping understand: Conversation Canada -- an international on-line academic newswire with a huge audience -- has had participation by faculty here. Recent contributions include pieces on Canada’s shameful history of sterilizing indigenous women; on federal back-to-work legislation; on Trump and populism; on UofS-led solutions to Canada’s water issues. As an institution, we just surpassed the one-million readership mark. But we can do more in this regard, and I urge all of us to weigh in publicly on the issues that matter, and for which we have unique expertise and perspectives.

You might be thinking that, with all I’ve said to this point, the humanities, social sciences and fine arts are being devalued, overlooked, and marginalized. Many employers, however, regard them as more important now than before – another finding of RBC’s Humans Wanted report. (And the majority of successful Silicon Valley high-tech startups by Canadians are led by people with humanities degrees, in the so-called C100 group). All innovation requires good communicators. The innovation curve is raising deep ethical issues in I.T., in Medicine, in business. It will require legal expertise. It will need people trained in philosophy to understand the ethics of a digitized economy; public policy influencers to understand how to respond to it; communicators and political scientists to help other countries learn from advances in crop techniques. In an increasingly globalized economy, a facility with languages is of paramount importance and widely coveted. It will be important to engage with the ethical issues around vaccines, the communications challenges that contribute to global food and water insecurity, the design thinking that will strengthen urban planning for future generations. Understanding Islamic culture, belief and history -- and the political and spiritual complexities attendant on them -- will make a greater difference to the globe’s well-being and to the goal of eradicating Islamophobia than many of the traditional scientific disciplines will. These aren’t vague predictions of the future value of the humanities, social sciences and fine arts: Canada will not improve without people trained in them.

And the same can be said more locally. The MoU we signed last year with the City of Saskatoon (all great cities need great universities -- try to think of a great city that doesn’t have one) identifies many challenges Saskatoon faces that can be helped by USask researchers in public policy, urban planning, the social determinants of health, Indigenous studies, political studies, community health and epidemiology, economics, history and so on – in short, the broad range of social sciences and humanities. On the artistic side – our agreements with the SSO and the Remai Modern are operational, each a first of its kind in the country as well. As our UPlan states, we will “Foster, expand, and diversify local, national, and global partnerships—with governments, businesses, and civil society in rural, northern and urban communities—rooted in reciprocal learning and the co-creation of knowledge.”

On the artistic work side, faculty from a number of parts of the university received almost half-a-million dollars in funding from the Digital Strategy Fund of the Canada Council for the Arts that brings together the human resources of the University in arts and digital technology to improve the digital capacity of the provincial arts community and the-not-for-profit sector in general – likely the largest grant from that Fund, and likely the largest grant ever received by the fine arts on this campus.

In this country, one of the greatest of challenges, and the greatest of opportunities, is Reconciliation. Universities have an enormous role to play in achieving this goal. Numbers tell part of the story. Twenty-three percent of non-Indigenous Canadians hold a university degree; eleven percent of Indigenous Canadians do. The cost of that education gap in this province alone has been pegged at $1.1B annually – in a commissioned study by one of our faculty members, by the way. That other gap I mentioned – between the large number of jobs in this province requiring a university degree and the lower number of people having one -- can be solved simply by raising the university degree attainment level of Indigenous people in Saskatchewan to that of non-Indigenous people. We continue to do our part by enrolling higher numbers of Indigenous students each year and supporting them for success at graduation and after. But we know we need to make fundamental changes to what the university is doing, and our Vision commits us all to that: We will be an outstanding institution of research, learning, knowledge-keeping, reconciliation, and inclusion with and by Indigenous peoples and communities. So does our UPlan. “Indigenization” runs through all of it – it is not just one commitment among several – and touches virtually every aspect of what we do at this university. It is that way because elders, knowledge keepers, and Indigenous community leaders supported and informed its design, and in the fall gifted it an Indigenous title: Nakanitan Manacitowenik – to lead with respect. We must make good on that as well.

The College of Law will review and develop policies and practices that are respectful of the diversity of Indigenous groups and that honour Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers. Law now requires students to take a first year course in Indigenous relations and history. Its program in Nunavut is in its second successful year. The College of Pharmacy and Nutrition has enhanced teaching and learning practices through the development of Indigenous curricular competencies within their learning community, and is establishing a transfer credit MoU with the Saskatchewan Indian Institute of Technologies and FNUC. The College of AgBio is establishing an elder-in-residence program. Dentistry is establishing a network of seven special care clinics serving high-need communities throughout Saskatchewan. Engineering is building respectful relationships with Indigenous communities, advancing unique opportunities for sustainable infrastructure in rural, remote and Indigenous communities, and starting a first-year access program to encourage Indigenous student participation and enrolment. Arts & Science will transform its existing faculty complement with a total of thirty new hires of Indigenous scholars over the next ten years, putting the faculty complement on par with the overall Indigenous population in the province. It is implementing an Indigenous learning requirement for all students for 2020. The Western College of Veterinary Medicine is increasing Indigenous graduate student funding and is growing its engagement and community outreach.

The Vice-Provost Indigenous Engagement leads a committee on anti-racist, anti-oppression education and research, and on Land- and Place-Based Education and research. We have MoUs with the FSIN, the STC, and with Canadian Roots Exchange. I am signing an MoU in Prince Albert with the Grand Council later this month. We co-hosted the FSIN Post-Secondary Forum in the fall. I spoke at the FSIN Assembly in February as our MoU with that organization commits the president to doing – the first time a USask president has spoken at that event. Three of the 11 members of our Board of Governors are Indigenous; our Indigenous faculty and staff numbers continue to increase. But we have much more work to do with and for Indigenous communities, and we are committed to doing it. Changes such as these must continue.

Whether or not Canadian universities meet these challenges will affect the quality of their programming, their levels of public support, their student enrolments, their relevance to Indigenous people, their research productivity, their funding both private and public, the level of innovation in Canada, and ultimately – in a post-truth world -- the moral fabric of the country and the globe. If we could control all the external forces I’ve mentioned here, change would not be an imperative. But we cannot, and change therefore is. It’s no longer a question of “if” we change, but “what” we change; no longer “why” we should change but “how” we should change.

All of this is why our university governs itself not only on the basis of what we want to be but what the world needs us to be. Our new university plan is titled “The University the World Needs” and is outward-focused for the reasons I’ve stated here. It is a bold and ambitious plan different from those of other universities in its emphasis on connecting with the needs of a city, province and country that have much to provide the world. Our role as a major research university, gifted with a unique scientific infrastructure and talent, exemplary professional colleges and programs, and a wealth of arts programs and talent, is central to the success of Canada’s innovation agenda, and to building a strong and globally influential future. If we agree to embrace change and participate in innovation, and commit to governing ourselves accordingly, we have all the features necessary to contribute with confidence to a better and more sustainable world.