State of the University Address

General Academic Assembly 2022 - A Post-Pandemic Look Ahead

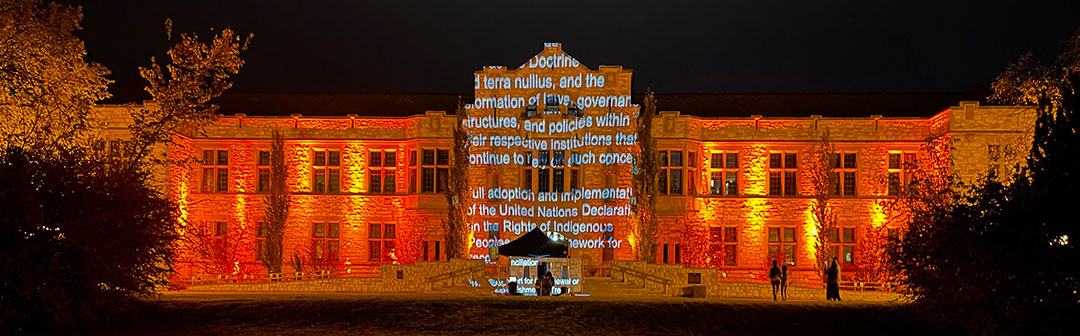

By Peter StoicheffI acknowledge that I am speaking from Treaty Six territory and the traditional homeland of the Metis, and that we pay our respects at this important time in our collective history to our First Nations and Metis ancestors of this place, and continue to work hard each day, with increasing understanding, to reaffirm our relationships with one another.

I appreciate this opportunity, offered once a year by the General Academic Assembly address legislated through the University of Saskatchewan Act, to reflect on the university’s recent past and its clear and promising future. To those here in a restricted capacity setting; and to the many of you joining on-line as well – thank you very much for devoting your valuable time to this event, which I continue to believe is an important one in the history of the university.

To say that the recent past has been a time of change is an understatement. We have never in our 115-year history seen such rapid change undertaken by all of us, nor change that has been so successfully and confidently achieved by all of us. It could not have happened had we not worked so well together – collegial governance bodies, academic units, labour groups, student leaders, offices, institutes, centres, schools, labs, Indigenous partners and communities, private partners and more.

From the moment just over two years ago when we shifted on-line for thousands of students, and for many of our operations as a major U15 university, to now, when we’re re-acquainting ourselves with the richness of an in-person campus and learning environment, we have found ways (led by our outstanding Pandemic Response Team) to work across these many sectors toward a common purpose that speaks to the integrity and the mission of this great university. The pandemic is not behind us yet, but today we can nevertheless feel proud of what we have collectively achieved so far during this most difficult time.

We are a place that values a diversity of viewpoints, and we’re also a place that continues to work together creatively to respond to the pandemic, with no prior roadmap in place, for the greater good. As our mission statement says, “we have a well-deserved reputation for creativity, collaboration, and achievement.” It has never been on such good display.

Our university community has worked together to keep students and faculty and staff as healthy and safe as possible during the pandemic. We had a goal from the beginning – to avoid contributing to the rise of COVID cases in the province – and we continue to achieve it together through strong strategy, clear communications, broad and constant consultation, and informed decision-making. This led to health protocols in the pre-vaccine pandemic period; to a vaccination policy late last summer; to a vaccination mandate by the end of 2021 and, by virtue of all of that, to a 99 per cent vaccination compliance rate across a university of 30,000 people. This speaks to the positive outcomes a community can achieve together when its policies are confidently communicated, agreed upon, and evidence based.

But during the pandemic we have achieved far more than ensuring we did not contribute to the rise of COVID cases in the province. These achievements speak to who we are and what we do as a university that, as our vision statement says, “contributes to a sustainable future,” and to the importance of universities to Canada and to the world at this time.

Our researchers and health-care specialists have been supporting the province throughout the pandemic by serving in front-line health-care roles, providing expert analysis, and engaging in COVID-related research. Faculty, staff, alumni, and students have contributed to the province through vital volunteer initiatives too, directly supporting those in need with food drives, and by providing personal protective equipment, mental health supports, therapy dogs and more.

RESEARCH WITH PANDEMIC IMPACT

Our Global Institute for Water Security wastewater analysis team continues to monitor community COVID rates that give parts of the province crucial early-warning information. The Canadian Light Source synchrotron’s call for COVID-related proposals attracted scientists researching antiviral drugs.

Our VIDO lab’s vaccine candidate is in Phase 2 human trials. We are grateful for significant funding from all levels of government, and from the private sector, that has made a great difference in VIDO’s ability to continue to lead the country in this critical area of research. Its evolution into Canada’s Pandemic Response Centre is well-earned. Its pilot manufacturing facility is nearing completion. VIDO’s success also speaks to the importance of curiosity-driven research, which paved the way for it to be the first university lab in Canada to isolate the virus, design an animal model for it, and develop its vaccine candidate. Without prior decades of fundamental research, their current vaccine work would not have been possible.

Our many health-related disciplines continue to make important contributions to the well-being of the provincial population. Faculty, researchers, staff, students, and alumni have been engaging courageously and knowledgably with the public dialogue on vaccines and other health measures. They’ve emerged as spokespersons and as models for the benefits of evidence-based decision-making that a university can provide. The province has been well served by having our health-related colleges and programs and research here at this university. Our faculty, staff and students are helping secure the province’s safety during these most health-imperilled years of our history; and their graduates, serving on the front lines under extremely challenging conditions, have been key to the province’s ongoing recovery.

From the beginning of the pandemic, we said that we needed to come through it successfully, not causing case numbers to rise in a community of 30,000, which is effectively the equivalent of Saskatchewan’s third-largest city. We also said we should not lose sight of the many other features of our mission that needed to be realized. Our pandemic response should not be the only activity against which we measure our success – and it has not been.

Our student enrolments are at their highest point in our history. This would not be so if our faculty and so many others crucial to our academic mission were not performing at such an impressive level, and with such commitment. We were gifted an Indigenous Strategy last summer by Indigenous Elders and leaders – the first of its kind in Canada. We signed an agreement with Métis Nation Saskatchewan on Indigenous identity, and we renewed our agreement with Wanuskewin – an important step on its journey to World Heritage Site status and on our own Indigenization and Reconciliation journey. We signed a joint commitment with the City of Saskatoon to accelerate the transition to a green community, and continued our important work with the city on our Research Junction initiatives.

EDI, SUSTAINABILITY, AND MORE

We also created and approved our first university-wide Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Policy and our first Sustainability Strategy. Last year was the second in a row that we were ranked in the Top 100 overall and even higher in select categories in The Times Higher Education (THE) Impact rankings for sustainability – which ranked more than 1,000 universities around the world. Just last week, we received news that we are now ranked in the top 60 worldwide by the THE rankings for sustainability impact, in a list that includes 400 more universities than before. This is an extraordinary achievement and speaks to our commitment to the United Nations’ Sustainability Development Goals, and to how our university succeeds at addressing one of the most important challenges the world faces today.

Over the past year we received the highest amount of research funding in our history. We conducted a successful renewal and refresh of our Signature Areas. Our Department of Drama celebrated its 75th anniversary as the first in the Commonwealth; our Department of Music its 90th; our Crop Development Centre its 50th. 2021 also marked the 50th anniversary of Dr. Gerhard Herzberg receiving the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He worked here for 10 years that were crucial to his research achievements. In his acceptance speech, documented on a plaque in Nobel Plaza just yards from where I’m speaking to you today, he paid homage to the University of Saskatchewan. We can be very proud of our researchers inducted into the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences and the Royal Society of Canada, and those who received international recognitions as well. Our Huskies student-athletes have performed extraordinarily well during a very difficult season, with eight teams going to the national championships.

AT THE POINT OF RETURN, AND OF NO RETURN

Today we’re at the point of return – to the campus again, and to the many academic activities that we cherish and thrive upon. We’ve been waiting for this for over two years. We thought we were at this point a few months ago, and we almost were, only to be delayed by the Omicron variant. I thank everyone, and in particular the many staff who worked on the campus to keep it ready for a return, and our many thousands of students, for their contributions, patience and perseverance as we ensured academic excellence and the university community’s continued health and safety simultaneously.

We’re at the point of return; but we’re also at a point of no return. The world has changed during the last two years in fundamental ways, so having a goal of returning to what we were prior to the pandemic would be a collective failure of vision and leadership. To be a university that’s responsive to what the world needs means understanding what has changed in the world over the last two years and what the post-pandemic world needs of us.

As places of learning, universities must be instructed by the pandemic and use that learning as an imperative for change. This doesn’t mean changing who we are. It doesn’t mean changing our mission, vision and values. But it does mean changing elements of what we do and how we do it. Together we have the opportunity to re-evaluate our role with the communities we serve – our students, the city, the province and beyond.

If the pandemic is revealing anything, it is that humanity’s healthy future depends on evidence- and data-based scientific truths being widely circulated and understood. High infection and mortality rates are a direct result of widespread misunderstanding, deliberate misinformation, skepticism of information, and a politicized rejection of scientific truths. I submit that addressing these challenges lies directly in the domain of a university such as ours.

It was an historic challenge for scientists to identify and understand the COVID-19 virus, and to design vaccines to fight it effectively. Decades of curiosity-driven research and a swift focus on vaccine development and manufacturing enabled by it saved millions of lives worldwide. But the even greater challenges to health and prosperity worldwide, it turns out, were unexpected and different. Science did what it was called upon to do, but its success was too often thwarted by a mistrust of authority, of truth, and of its messengers. We will continue to rely on scientists to predict future viral threats and to create vaccines for them – hence the significance of VIDO becoming Canada’s Centre for Pandemic Research, and of being supported by CEPI (the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) whose mission is to ensure the world is well positioned to fight the next pandemic.

But what we will also need is the public policy, communications and educational strategies, the political trust, and the collective sense of purpose that, to date, has been lacking globally. Together, universities need to identify those areas of urgent public need accurately, and deliberately address them, in academic programming and in research.

This work is largely in the purview of the social sciences, humanities and fine arts. If ever there was a need for this expertise – in history, political science, policy, ethics, equity and diversity, religious studies, education, law, business, anthropology and so on – it is right now. The pandemic has revealed we need critical thinking, acquired and sharpened at universities such as ours, more than ever before, in order to lead public opinion, not follow it.

THE UNIVERSITY THE POST-PANDEMIC WORLD NEEDS

And the pandemic has also revealed that universities need to reinvigorate their roles as thought-leaders, engaging with the most important issues of our time, not only in the classroom and the lab, but in the public sphere. At this moment in our history, this is what it means to be the university the world needs, and with our unique combination of disciplines and talents, so many of them in the humanities, fine arts and social sciences, we must continue to step up and supply it.

We’re glad to be gradually returning to campus, but our two years of remote delivery have shown us we have the technology to serve learners in distant communities, or who lack the means to move to our campuses. It will be one way in which we can address the inequities the pandemic revealed.

The effects of a digitized economy that became apparent shortly before the pandemic, and which this university identified and was alert to, have only been accelerated: the need for people to receive education at many different stages of their lives; the need for upskilling, reskilling (and “greenskilling”) in a workplace with constantly evolving demands of its employees; the need for shorter times to completion of degrees; the need for microcredentials and other forms of attainment that do not require the traditional several years of commitment (which we’re also achieving through a streamlined program approval process); the need for experiential learning opportunities, and for international programming and research opportunities. In fact, the Conference Board of Canada, in its report of March 3rd this year called Beyond the Classroom: The Future of Post-Secondary Education Has Arrived, details many of these, encouraging the post-secondary sector to creatively ensure these learning options that currently exist on only a small scale are expanded.

The encouragement isn’t coming only from there: students are signaling they require greater flexibility in programming and credentials, as are graduates and others already in the workforce or wanting to re-enter it, to whom we must attend. Our University Plan 2025 calls attention to these; the pandemic has shown we identified them accurately, and has increased the urgency for us to respond. To date, we are making progress on each of these. I encourage us to continue that good work, and to making it a priority.

These expectations for curriculum redesign don’t stop with students past, current or future, or with conference boards. They are held by local employers as well, many of whom are our alumni. They see us as their source for talent, and our students see them as key to leading prosperous and fulfilling lives. The external engagements we conducted at the beginning of our Post-Pandemic Shift Project revealed that employers’ needs for more interdisciplinary education, experiential learning credentials, and the human skills of communication and leadership have intensified through the pandemic – and they look to us to understand those needs and respond to them. If we don’t, the signs are clear these requirements will be satisfied elsewhere, in an increasingly competitive environment on this continent.

CULTURE OF INNOVATION

In its annual assessment of the fastest-growing companies in Canada, the Globe and Mail recently listed four in Saskatoon, each of which has close ties with our university either because they employ many of our graduates, because they were started by them, or because they benefit from the kind of expertise we can supply. They’re one part of a vibrant Saskatoon innovation culture that is the second-fastest growing in the country. Other parts include Innovation Place research park; the fact that Saskatoon has seen a 15-fold venture capital investment growth in recent years, the fastest on the continent; and the fact that our university is here, working in a close relationship with the city, educating thousands of creative and innovative graduates annually.

You can add to that our world-class infrastructure that includes our Canadian Light Source and VIDO labs, our cyclotron, our Global Institutes for Water Security and Food Security, our SuperDARN radar network, as well as the fact that we have 17 colleges and schools from which employers can draw expertise and creativity. The sum of all this, concentrated in this medium-sized city, is formidable, and puts us and Saskatoon on the cusp of even greater influence and impact on the local economy.

At the same time, Canada’s innovation performance, the key to our collective future of prosperity and upward mobility, is poor relative to our OECD partners. The percentage of youth not in employment, education or training is high – our ever-increasing student numbers prove we’re responding. The rate of master’s and PhD attainment in Canada is low – we are responding as well. Labour market gaps, especially for Indigenous peoples, are too large – we have a critical role to play there, and we have been playing it. One area of real growth in Canada is in immigration – we have a critical role to play there too, attracting the best talent from around the world because of who we are, what we do, and how well we do it. Our international student numbers continue to climb, one measure of our positive impact in this important area.

Our role in this innovation ecosystem is critical. Economic growth in this country is predicted to be stagnant, but not in Saskatchewan. Keep in mind that we are the university named for a province that has more than 40 per cent of Canada’s arable land; a third of the world’s potash resources in a time of global food security crises; one quarter of the world’s high-grade uranium supply at a time of global carbon fuel reduction; at least a 10th of the world’s rare earth and precious minerals supply at a time of unprecedented demand; and enormous freshwater resources at a time of world-wide clean water shortages. Saskatchewan is the country’s largest supplier of canola, peas, and lentils at a time when the future of the world’s population depends on plant-based protein as never before. No other province can boast these timely attributes that are so important to the world, and no other university has the combination of attributes to be as central as we are to their future success.

Playing our role in the local, regional and national innovation ecosystems will be crucial here. They will not thrive without us – a major research-intensive, medical-doctoral university is their most unique feature. We must ensure we support entrepreneurship and “scaling-up” of Canadian-based firms through our programming, research and external connectivity. With many thousands of entrepreneurship-minded students and faculty, it remains for this university to be deliberate about an innovation strategy – that is, translating knowledge into impact – that extends across our research and programming activities.

Innovation is woven throughout our University Plan 2025, where we commit to developing the “knowledge and skills to thrive”, to “moving discoveries into the world”, and to being “a go-to resource and partner” for the people of Saskatchewan and beyond. And that’s what we’re doing, by encouraging entrepreneurship-focused curricula, establishing a campus incubator for entrepreneurship, and working more closely with Innovation Place to develop an innovation corridor that combines our respective contributions and potential.

POST-PANDEMIC SHIFT PROJECT

Foreseeing early on in the pandemic the need for imminent changes, but as yet uncertain about what they would look like, we began our Post-Pandemic Shift Project. I thank the many who led it, and the many across the university who participated in its work. It identified the new features that would be critical to our success in the areas I just mentioned.

The project showed that we will need to lead differently, and be less hierarchical, more adaptable and inclusive. We will need to innovate, and encourage risk-taking and experimentation. We will need to engage with each other differently, focused on equity, ensuring that compassion and mutual respect drive our work together, underpinned by the principle of Wahkotowin that teaches us that our interdependence will determine our future. And we will need to support each other, ensuring our collective mental health and wellness.

These shifts in how we lead, innovate, engage and support give us the foundations for our post-pandemic university that responds to what the world needs of us. I emphasize the importance of this work by our colleagues, and encourage all parts of the university – colleges and schools, departments, programs, leadership offices, all of us – to ask ourselves, with each decision we are making, does it mean we are leading differently?; does it mean we are being more innovative?; is it based on being equitable?; does it mean we are supporting each other? Or does it mean we’re merely returning to the way things were prior to the pandemic, just because that’s what was familiar to us?

In the General Academic Assembly address I gave in 2016 I proposed that great universities have high levels of “of connectivity (among programs, researchers, industry, communities), diversity (among students, staff, and faculty), and sustainability of all kinds including environmental and cultural.” These became pillars of our University Plan 2025. In the intervening years, together we have been achieving them. In setting ourselves the goal of responding to what the world needs of us, we are increasing our connectivity. With our EDI Policy we are increasing our diversity and inclusion. And with our Sustainability Strategy and Action Plan, reflected in the recent THE Impact rankings, we are contributing to sustainability.

Now we are going further and setting our sights on how to be an excellent, innovative university for a post-pandemic world. Our response, together, to the pandemic demonstrates the value of this university to the province and far beyond it. We will continue to contribute to economic recovery; to internationalization; to talent attraction; to leading on sustainability and climate change; on equity, diversity and inclusion. These are extraordinary achievements, and without relaxing our commitment to them, we should acknowledge them.

SUPPORTING UKRAINE

I want to end with remarks on the devastating military invasion of Ukraine. Our province has many citizens of Ukrainian descent, we conduct programming and research related to Ukrainian culture, language, politics, and history, and we have partnerships and student exchanges with institutions in Ukraine. And most importantly, given the increasingly dangerous world we’re now in, a university is fundamental to everything that invasion contravenes and opposes. At each convocation I state that “a university is a wonderful thing – a great experiment in the ongoing conversation we call democracy. Universities are crucial participants in that conversation. We are reminded daily that we are so fortunate to live in Canada and to have the freedoms we enjoy.”

The shocking events that have unfolded in Ukraine over the last several weeks are troubling for all of us, and particularly for our many Ukrainian and Russian university community members. We are reaching out to help. We have many experts who have weighed in on the consequences and realities of the Russian invasion. We have created ways to fundraise for Ukrainians in crisis, including through the Nasser Family Emergency Student Trust and the Marquis Hall support for the World Central Kitchen that is on the front lines providing fresh meals to Ukrainians in need.

We are staying in touch with each of our Ukrainian students and helping them with their immigration status, mental health, potential program interruption, and more. We are staying in touch with each of our Russian students as well. I have written personally to my counterparts at the Ukrainian universities with which we have formal relationships. The College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies is facilitating the hosting of displaced research trainees. We are connected with the Tri-Agencies’ Special Response Fund for Ukrainian Trainees.

We are working closely and continuously with the City of Saskatoon and the Open Door Society, as well as with the Government of Saskatchewan, which is partnering with the Ukrainian Canadian Congress of Saskatchewan, with Ukraine and with the federal government to co-ordinate the intake of Ukrainian refugees here. And we are also about to implement a “scholars and students at risk fund” to help provide a haven for international students facing challenges to enter or remain at USask through the delivery of bursaries. This fund will aid those emerging from humanitarian disasters, including Ukraine and neighbouring nations affected by the current war, and other international situations that might arise, circumstances which pose immense financial challenges to students wanting a new start or to finish what they have begun.

Let me thank you all for attending this year’s General Academic Assembly address, and for listening to these words of encouragement regarding the role we have played during the on-going pandemic, and to our place in an eventual post-pandemic world. As we close in on the end of another Winter Term, I wish every member of our university community well, and offer my hopes for a healthy and fulfilling spring and summer for each of you.